‘Make’ Procedure under the Defence Acquisition Procedure 2020 (DAP-2020), is publicised as the most critical, towards building a robust defence industrial ecosystem and tapping the emerging dynamism of Indian industry in the defence sector; and in words of many in the Ministry of Defence (MoD), boost ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ and ‘Make in India’. However, after spending years chasing various DAP/DPP (defence procurement procedures), the juxtaposition of the contrast between theory and practical, the current Make Procedures, in my opinion, fall short of the expectation; and one of the reasons behind this is incentive, which seems to be missing.

The incentive problem in defence procurements, as highlighted by former chief economist of Federal Communications Commission William P Rogerson, is an outcome by four underlying economic characteristics of any defence procurement process. 1) Research and Development – Innovation is as important as the product and also is an inherently difficult product to purchase, thereby creating a need for providing incentives for innovation. 2) Uncertainty – Internal uncertainty, due to technological unknowns in design of new weapons and external uncertainties in the demand, due to changing threat, availability of substitute weapons and availability of funds. 3) Economies of scale of production – relatively small quantities purchased of most weapons, it is uneconomical to have multiple firms produce same weapons system. 4) Government is sole buyer – Creating a major ‘hold-up’ problem; at R&D phase the firms worry, if they will ever recover their sunk expenses and at production phase, firms worry if they will ever recover investments, as product has little use outside the defence industry.

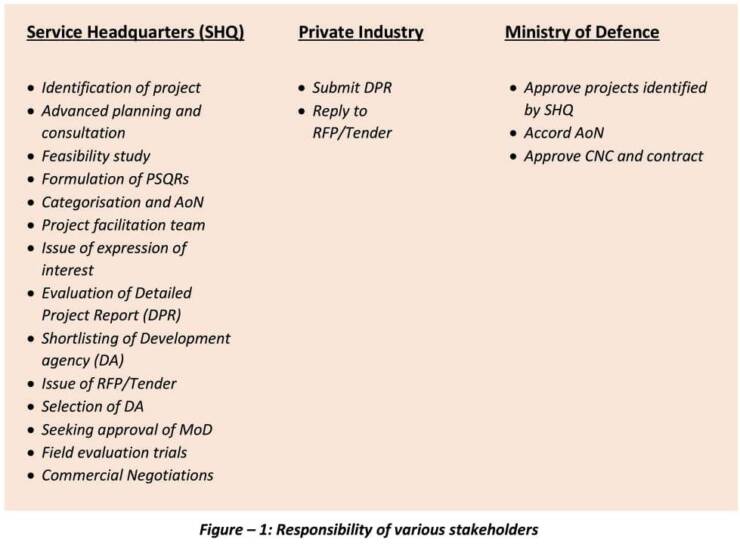

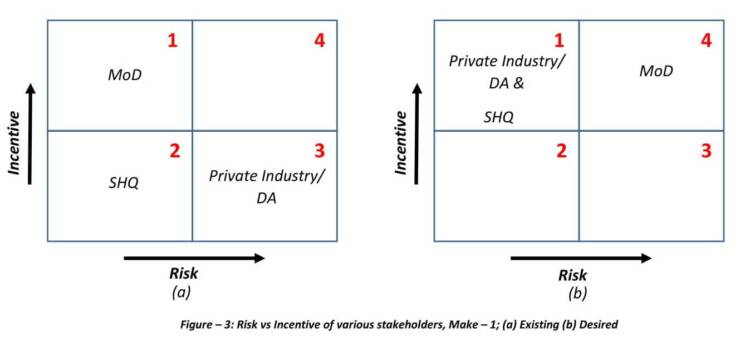

The three stakeholders listed in DAP under the Make-I procedure, Service Headquarters (SHQ) while shouldering the maximum responsibilities (Figure 1 refers), have the least incentive. The incentive for SHQ would be the timely delivery of the product meeting all Staff Qualitative Requirements (SQRs). Going with the past precedence of projects undertaken under the Make category and India’s defence industrial base (DIB) far away from being mature, chances of both the incentives fructifying, are greatly reduced.

To make it worse, ‘Make’ cases are challenging to pursue, compared with either ‘Buy’ or ‘Buy & Make’ cases. Figure 2, depicts the difficulty level of the three main categorisation, from Easy to Difficult. ‘Buy Global/Government to Government’ (G to G) is the easiest (and fastest) while ‘Make’ is the most difficult (and slowest). Difficult here would mean – multiple agencies, multiple approvals, prolonged monitoring, monumental paper/file work, higher chances of failure and extended timelines for project fructification. It is thus no surprise that SHQ has acquired most big ticket purchases via ‘Buy’ route and in it the easiest – G to G. Rafael aircraft, Hercules transport aircraft, M777 155mm Howitzers, Apache helicopters, S400 Surface to Air Missiles, all have been procured via the Buy – G to G route. On the other hand, Make – I has only two projects listed under it, totalling only Rs 3,665 Crores. So the risk for SHQ and the incentive are quite low for pursuing cases under Make – I.

The government, the second stakeholder, wants Make – I to succeed as a successful project will give its flagship program (‘Make in India’ and ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’) the necessary impetus. Other than political dividends, it will increase employment in high skill sector (in the long run), reduce import bill and increase the defence industrial base. Future exports of the product and or technologies developed under the project would further reduce development cost. So incentive are higher, both long and short term.

However, while having higher incentive, the government risk under ‘Make – I’ is quite low (Figure 3 refers). The government’s financial is limited to a maximum of 70 per cent of the cost of the prototype up to a maximum of Rs 250 Crores (to be paid in phases). Further, each phase payment is again secured against Bank Guarantee (BG) provided by the private industry/ development agency (DA), amounting to 20 per cent of the cost of the prototype. The 70 per cent share of development is further hedged against complete ownership of all tangible assets created under the project and besides, ‘Government – Purpose Rights’, ‘Unlimited Rights’ and ‘March in Rights’, on all the IPs developed under the project.

Private industry/DA, the third stakeholder, is on a very tenuous wicket. While the incentives are not gargantuan, the risks somewhat are that way. Besides bearing 30 per cent of the development, and reduced IP rights, it will also have to share the production, with L2/ L3 (second/third lowest bidder), thereby eating away his profits. This is in addition to the encumbrances of BG, payment delays, bureaucratic hurdles, which are Omnipresent in all defence contracts. Even the 70 per cent which it will receive in phases, will have to pass the test of relevancy, financial prudence, reasonability and relationship, every time. So maximum tangible risks and greatly reduced perceived incentive.

One of any government’s primary roles is to promote investment in research and development (R&D). In the defence sector, where the government is the sole buyer and also largest beneficiary, this responsibility assumes a larger role. Government has to realise that, other than protecting its investments; existence and safeguarding of defence businesses, protecting commercial interests of DAs, provision of skills and competencies of the defence value-chain also, are inescapably parts of its role (The Defence Industrial Triptych – H Heidenkamp, J Louth and T Taylor).

The government has to be the big brother in the Trinitarian and take the largest share of risk, which presently is shouldered by the private industry/DA. The share of investment in prototype development has to be 100 per cent from the current 70 per cent. The government need to ensure that innovation by the DA is rewarded through profits on the production and product upgrades. The prospects of earning profit, gives the defence industry /DA an incentive to exert their best efforts at design/ innovation phase (William P Rogerson). The ask is similar to what the government provides to the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) in all Make projects pursued by them; private defence industry is as important to the nation as public sectors and need to be supported via tax breaks and subsidies, to encourage them to invest more of their own funds in defence innovation. Unless, this realisation dawns, ‘Make – I’ will not ‘Make’.

-The writer is voluntarily retired from active service after more than 21 years of commissioned service. He is an alumnus of Naval Academy (first course 10+2 X) and Defense Services Staff College and a specialist in Anti-Submarine Warfare. Presently, he is pursuing PhD in Defense Industrialization and Exports (India) from Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT). New Delhi. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda