Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the court of emperor Chandragupta Maurya wrote in his book Indica that the Mauryan Army consisted of an astonishing 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, 9,000 elephants and an unnamed number of chariots. What’s unique about this vast juggernaut is that it was not a militia but a standing army drawing regular pay and supplied by the government with arms and equipment. More than 2,300 years ago, it was this Mauryan army that consolidated the first political empire that controlled almost the whole of the Indian subcontinent.

Using this massive army, Chandragupta not only conquered the Indian heartland up to the borders of the Tamil lands, but also extended it to the natural boundaries in the north up to eastern Persia and the Hindukush mountains. When the Greeks led by Seleucus Nicator attacked India with a view to take back the areas that had been formerly under Alexander’s nominal control, Chandragupta routed the Greeks, inflicting a resounding defeat. Seleucus had to surrender the four satrapies of Aria (Herat), Arachosia (Kandahar), Paropanisadiae (Kabul) and Gedrosia (Baluchistan) all of which became part of India.

Why is the study of the Mauryan army relevant today? A centralised empire with a powerful military is not only the surest defence against external aggression, it is also a pre-condition for internal stability. Military might is therefore the primary guarantor of peace and prosperity.

Beginning of political consolidation

The collapse of the Persian Empire on the battlefield of Arbela in 331 BCE served as an eye opener for India’s fractured ancient kingdoms and republics which keenly felt the necessity of having a centralised national government to protect life and property.

In 326 CE, Alexander’s massive army was mauled by the Indian king Porus in the Battle of Hydaspes, forcing the Macedonians to retreat towards the sea in order to get back to their Mediterranean homeland. From Punjab all the way south to the sea, Alexander’s army had to fight its way through hostile Indian kingdoms. The bitter resistance put up by the Indians led to numerous casualties and the destruction of Alexander’s entire cavalry. This enraged the Macedonians who then carried out brutal and large scale massacres along the entire route.

It was these large scale massacres that helped Chandragupta and his advisor Chanakya to later mobilise these north Indian kingdoms, republics and tribes to subsequently achieve a political unification of India. These states had fought valiantly but suffered terribly at the hands of the invaders due to their disunity. As such, when Chandragupta spoke to them of the need for a strong and unified India, they were in a mood to listen and do something about ensuring they would not submit to such savagery again.

Military transformation

A change in political outlook was accompanied by a corresponding change in the military system or defensive arrangements of the country. The military administration of the Mauryans was very elaborate and efficient. The highest officer of the army was the Senapati or commander-in-chief, who got a salary equal to that of a chief minister. Megasthenes writes that there was a regular war office for military administration. There was a commission of 30 members divided into six boards, each consisting of five members. In the Arthashastra, Chanakya also seems to refer to these boards when he says that each department shall be officered by many chiefs. Each board had probably a superintendent, who seems to have been identical with the Adhyaksha of the Arthashastra.

Board I

The first board was in charge of the navy, and worked in co-operation with the admiral who was probably identical with the Navadhyaksha of the Arthashastra. This officer performed all the duties relating to ships such as hiring of ships to passengers, collecting toll from merchants, arrest of suspicious persons and destruction of hinsrikas or pirates. The ships were maintained by the state and were not restricted to rivers but ventured out to sea. These regulations clearly show that there was a considerable ocean traffic in Maurya times.

Board II

The second board was in charge of the transport commissariat and army service, and worked in cooperation with the superintendent of bullock trains who was probably identical with the Godhyaksha of Arthasastra. The bullock trains were used for transporting engines of war, food for the soldiers, provender for cattle and other military requisites.

Board III

The third board was in charge of infantry, whose superintendent appears to have been the Pattyadhyksha. Arrian has preserved an account of the way in which the Indians in those times equipped themselves for war: “The foot soldiers carry a bow made of equal length with the man who bears it. This they rest upon the ground, and pressing against it with their left foot thus discharge the arrow, having drawn the string far backwards: for the shaft they use is little short of being three yards long, and there is nothing which can resist an Indian archer’s shot, neither shield nor breastplate, nor any stronger defence, if such there be.

In their left hand they carry bucklers made of undressed oxhide, which are not so broad as those who carry them, but are about as long. Some are equipped with javelins instead of bows, but all wear a sword, which is broad in the blade, but not longer than three cubits, and this, when they engage in close fight, they wield with both hands, to fetch down a lustier blow.”

Board IV

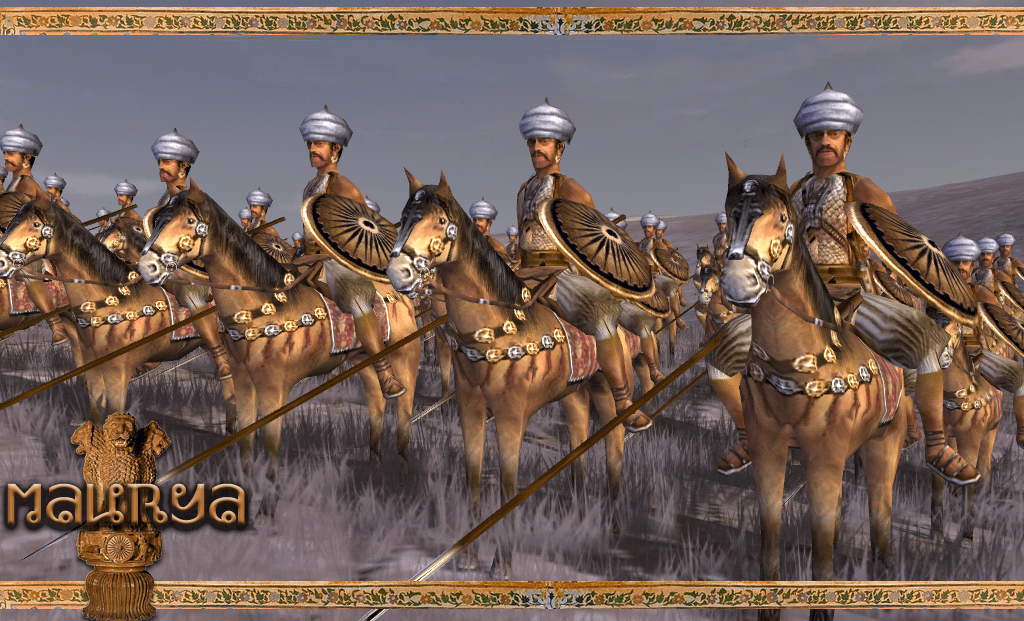

The fourth board was in charge of cavalary, whose superintendent appears to have been the Asvadhyaksha. Each horseman was equipped with two lances and with a shorter bucker than that carried by the foot soldiers. The horses of Kamboja and Sindhu were regarded as the best.

Board V

The fifth board was in charge of the war elephants whose superintendent was probably the Hastyadhyaksha. By the time of Alexander’s incursion into India, elephants had taken the place of chariots as the foremost tactical arm of the military. The elephant is described as crushing infantry, cavalry and chariots with equal ease. Megasthenes records that Chandragupta had a total of 9,000 elephants in his army, which is more than the total number of chariots in his army, so it is evident that the elephant had become a very important weapon by the time of the Mauryan Empire.

Chanakya writes that it is upon the elephants that the destruction of an enemy army depends. The elephants carried three warriors with bows and one mahout. The elephants would have been used both to screen the army and to break through the enemy army and inspire terror in enemy soldiers. The risk that the elephants would cause confusion in the friendly ranks as well did of course exist, but often the strategy of Indian armies revolved around the fact that the enemy army would be broken up by the elephants’ charge, and could then be mopped up by the rest of the army.

Board VI

The sixth board was in charge of the war chariots, whose superintendent was probably the Rathadhyaksha. Throughout the history of Indian warfare, the chariot seems to have reigned supreme, and its history goes all the way back to the early Vedic days. Mahapadma Nanda, the predecessor of Chandragupta, had possessed 8,000 chariots, but after the miserable performance of King Porus’ chariots – which got stuck in the rain-soaked earth – against Alexander, they seem to have fallen out of favour in the Mauryan army.

Astute observers like Chandragupta and Chanakya would scarcely be expected to blindly follow the war tactics that were clearly outdated. The Mauryan army may have maintained a symbolic chariot corps for parades and pageants and for transporting the nobility.

Technologically advanced

Unlike the Hindu empires of medieval India which were caught wanting in equipment and modern war tactics, the Mauryan army had the latest technology of its times. India even before Chandragupta was an innovator in the military field. For instance, Ajatashatru, who ruled Magadha nearly 150 years before Chandragupta, invented two weapons used in war called rathamusala (Scythed chariot) and mahshilakantaka (engine for propelling big stones). Chandragupta’s close friendship with the Greeks ensured that he had the best of the both worlds.

According to historian Richard Gabriel in ‘The Ancient World’, “By the Mauryan period, the Indians possessed most of the ancient world’s siege and artillery equipment, including catapults, battering rams, and other siege engines. A distinguishing characteristic of Indian siege and artillery practice was a heavy reliance on incendiary devices such as fire arrows, pitch pots and fireballs. These were even a manual instructing how to equip birds and monkeys with the ability to carry fire inside buildings and on to rooftops.

There were six troop types in the Mauryan army: The main warriors, or Kshatriyas, which were the backbone of the army; mercenaries and hired help who were paid for their services; troops provided by guilds (caravan guards and watchmen); troops provided by allies or deserters from the enemy army; and tribesmen who were found in the hills and forests around the lands.

This mix of an army was incredibly large with even minor kings in the Mauryan Empire having an army well into the thousands with chariots and elephants to boot, simply because the manpower of the Empire was massive and India had a plethora of gold and metals and the means to produce weapons on a large scale. The plains around India were exceptional for cavalry.

Battle tactics

The tactics of the Mauryan army was a mixed group army. Instead of having one unit of all spearmen, they combined several groups of weapons and trained them to work together. The basic unit was three archers or spearmen riding an elephant, supported by three cavalry men with javelins and spears and five swordsmen. The twelve man (and one elephant) unit assembled in groups of three and formed a company and three companies were one battalion.

Most soldiers were armed with traditional weapons, but their armies had very few archers because the bows they used were so big they took a long time to fire, even though the power they had was enough to pierce any armour. Lances, spears and throwing javelins were the main ranged weapons of the army.

Chanakya has written on when to mobilise different kinds of troops. In his view, before deciding on what kind of troop, i.e. standing army, territorial army, militias, friendly forces etc to be mobilised for the campaign, it is absolutely necessary to find out what kind of troop the enemy is using, and which troop would be best suited to defeat it. According to him, the standing army should only be used when it is absolutely necessary to do so and when there are no threats of internal rebellions, otherwise, other troops such as militias should be used.

Soldiers were honoured

More than 2,000 years before Napoleon Bonaparte said that “an army travels on its stomach”, the Indians had internalised this maxim. Megasthenes writes in the Indika that the soldiers of the Mauryan army were so well paid that they maintained others on their wages. The picture of the well-paid soldier is also borne out by the Arthashastra, where his salary is given as 500 panas, considerably more than that of the clerk (120 panas) and that of a servant (60 panas).

Angelos Chaniotis writes in Army and Power in the Ancient World that the commander-in-chief or senapati was paid 48,000 panas, which is ninety-six times the salary of the soldier and presumably this high salary was intended to buy his loyalty. Superintendents and commanders received a more reasonable salary, between 2,000 and 8,000 panas.

The loyalty of officers was tested from time to time, one form of test being the appointment of more than one commander of a wing.

Salaries were augmented by booty. For the killing of an established warrior 10,000 panas, for a chariot warrior 5,000 panas, for a horseman 1,000 panas, for the chief of an infantry unit 100 panas and for a soldier 20 panas were given.

The driving principle of the Mauryas was that the army will be loyal if it is paid a good salary and is honoured by the king.

Peace in the empire

Brigadier K Kuldip Singh writes in ‘Indian Military Thought’ that there is a consensus among historians that the history of India owes to Chandragupta a prodigious gratitude for adding a glorious chapter of gorgeous phenomena on an electrifying war of liberation, a vast empire enfolding the better part of India under one flag, and the systemisation of life, on which founded the invaluable national and cultural consciousness among the Indians of the subsequent ages.

Bimal Kanti Majumdar writes in The Military System of Ancient India that Chandragupta’s empire extended the limits of the Mauryan empire to the foot of the Hindukush and invested it with great responsibilities as Chandragupta at once entered into that scientific frontier sighed for in vain by his English successors and never held in its entirety even by the Moghul emperors of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

“It reflects great credit on Chandragupta and his successors on the imperial throne that they ably guarded the north-western frontier for over a century, and not a speck of dark cloud appeared on that horizon until their strong hands were withdrawn and the Mauryan military organisation showed signs of deterioration for more than one reason.”

Annihilation through Ahimsa

After Chandragupta, his son Bindusara proved an able ruler who consolidated the boundaries of the Mauryan empire. However, Bindusara’s son Ashoka set in motion events that ultimately led to the decline and fall of the empire. “Ashoka’s change of foreign policy and his other worldliness must have created some apathy to militarism, political greatness and material well-being,” says Majumdar.

According to many historians, Ashoka’s policy of dhamma was primarily responsible for the disintegration of the Mauryan empire. Rhys Davids though he admires Ashoka as a great leader nevertheless holds him responsible for the disintegration of empire. To quote him, “With all his evident desire to do the very best possible things, and always to be open to the appeals of the subjects he looked upon as his children, he left his empire in such a condition that it soon disintegrated and crumbled away.”

Critics point out two serious drawbacks of the policy of dhamma which led the empire to the path of disintegration.

On the one hand it was responsible for military pacifism. Some writers ascribe the downfall of the Mauryas to Ashoka’s policy of ahimsa or non-violence. Ashoka after the war of Kalinga did not wage any other war and instead of conquest of territories he began with the conquest by the dhamma. As a result of this the military strength of the Mauryan Empire declined. The military attitude was also absent from the minds of the people. Ashoka’s followers too followed the path of non-violence which further rendered the empire militarily impotent. It was due to this reason that the Mauryan empire could not survive long after Ashoka’s death.

The Mauryan empire was founded by a policy of blood and iron and could only be maintained by following the same policy. But by eschewing all wars and abandoning the aggressive imperial policy, Ashoka weakened the very foundation of the empire. The emperor even offered guidance and assistance to neighbouring kingdoms in their internal affairs. There is evidence that he gave them advice on occasions, and established philanthropic institutions in their dominions. In other words he regarded them as objects of religious conquest.

The lack of all military activities after the Kalinga War and the constant preaching of the great virtue of ahimsa by the emperor had a permanent effect, not only on the military organisation of the state, but also on the martial qualities of the people in general. The soldiers lost their skill and discipline and Indians generally became averse to war.

Dark clouds were looming in the North-Western horizon. India needed men of the calibre of Porus and Chandragupta to ensure her protection against the foreign menace. Instead, India got a dreamer.

Magadha under Ashoka frittered away her conquering energy in attempting a religious revolution. Whereas mighty Mauryan armies raised the imperial flag in the furthest corners of the subcontinent and tamed the fiercest tribes of Swat and Afghanistan, under Ashoka they were replaced by thousands of bhikshus (holy beggars) wandering around, seeking to preach non-violence.

The result was politically disastrous. Writes HC Raychaudhary in Political History of Ancient India: “The provinces fell off one by one. Foreign barbarians began to pour across the north-western gates of the empire, and a time came when the proud monarchs of Pataliputra and Rajagriha had to bend their knees before the despised provincials of Andhra and Kalinga.”

Endgame

Modern India has its own Chandraguptas and Ashokas. Under the dreamer Jawaharlal Nehru, India lost half of Jammu & Kashmir to China and Pakistan. Under Manmohan Singh, India was constantly attacked by terrorists pouring in from the badlands of Pakistan. His defence minister AK Antony crippled the defence forces through inaction on key weapons systems.

However, under rulers who adopted the Kautilyan approach towards diplomacy and war, India’s underlying strength rose to the surface. Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s decision to go nuclear led to a new military and diplomatic alliance with the United States, thereby weakening Pakistan’s hand and making China fear a two-front war. But more importantly, it raised India’s stock externally, leading to a huge inflow of investment.

Narendra Modi has taken the fight to the enemy’s camp. The Uri and Balakot surgical strikes demonstrated to the enemy that it will pay a heavy price for terrorism. National Security Advisor Ajit Doval’s statement that “one more Mumbai and you lose Balochistan” is not just a threat to Pakistan – it is an indication of how India’s new militaristic thinking will decide Pakistan’s future geography. Not just Balochistan, but Sindh and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa need to be turned into independent countries to cripple Pakistan’s ability to wage war of any type against India.

Destroying Pakistan is only a sideshow in India’s larger strategic game plan. Under Modi, India has started rearming in the pursuit of its natural destiny as a global military power in sync with its rise as an economic superpower. For, it is plain as water that a country that cannot protect its growing economy, food supplies, trade routes, merchant shipping fleets, energy pipelines and strategic metals remains a one-dimensional power that remains hostage to the goodwill of other nations.

During Chandragupta’s time, India was encircled by external enemies and fractured by internal divisions – a situation that is eerily similar today. It was the strong Mauryan army that defeated the Greeks and subdued the internal rebels so that the country was at peace and the people were able to go about their daily businesses without having fear for their safety.

Major General GD Bakshi writes in The Rise of Indian Military Power that the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) generated by the Mauryans transformed the socio-political order and unified India from a civilisational entity to a highly centralised empire which became the forerunner of the nation state that would form in India about two millennia later. It was the imperial Mauryan army that helped generate the idea of India as a civilisational state.

Bakshi adds, “The Mauryan Empire succeeded where the British Empire was to fail later – it secured a scientific frontier by securing the invasion routes in Afghanistan and Balochistan. The empire emerged in a multipolar environment of 16 huge Mahajanapadas in the Indian subcontinent that were constantly at war with one another. Hence the great relevance of its strategic outlook today.”

In terms of geography, the Indian republic is a much smaller entity than the Mauryan empire. But the core remains intact and that’s what matters. While the civilisational ethos is the foundation of the country’s re-rise, the Mauryan military system also needs to be studied and its strategies adapted to make India great again.

The author is a New Zealand based defence analyst. His work has been quoted extensively by leading Think Tanks, Universities and Publications world wide. The views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda.