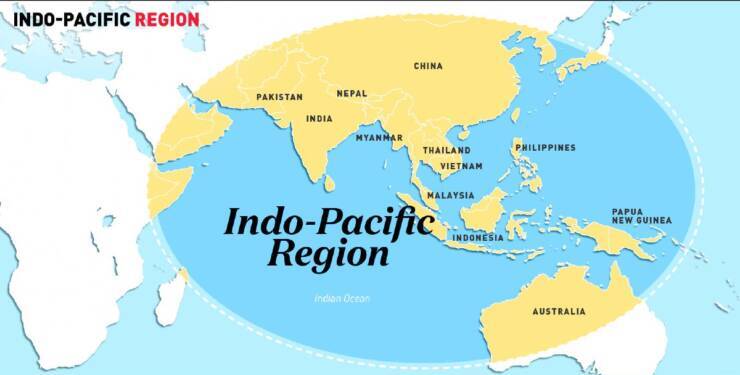

Historically, colonial powers considered it their prerogative to not only re-draw borders and create nations, but also to allot arbitrary geographic nomenclature to suit their geo-political designs. Post WW-II, it was America that decided to create a new entity—the Asia-Pacific—to establish its economic and security linkages with Asian nations like the Philippines, South Korea and Taiwan. The Asia-Pacific was further sub-divided into NE Asia, SE Asia, and Oceania.

For years, many considered ‘Asia-Pacific’ a discriminatory paradigm, because it appeared to terminate at the Malacca Strait and excluded the Indian Ocean littoral. As Asian economies boomed and economic and security links grew, across the Malacca Straits, a coupling of the Indian and Pacific Oceans became inevitable.

Proponents of the new ‘Indo-Pacific’ paradigm argued that it reflected the reality of economically resurgent China and India on either side of the Malacca Straits. Realists, also, saw this as a logical step in the US strategy to balance a hegemonic China, by drawing India into the same geo-political arena.

Today, the US unhesitatingly acknowledges that the Indo-Pacific is the “single most consequential region for its future,” and has shown its commitment to this new concept by re-designating its Pacific Command as the Indo-Pacific Command. Even distant Europe has been compelled, by the growing salience of this region, to get involved, and France, the Netherlands and Germany have released an ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy’ document, each.

In an interesting development, July 2021 saw an international group of warships, led by the British aircraft-carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, transiting from UK to the Pacific via the Indian Ocean, exercising with navies (including ours) en-route. This extravagant and ambitious demonstration of maritime power, by a diminished post-Brexit Britain, is a manifestation of its self-belief that it remains a ‘global power,’ that needs to establish a ‘military footprint’ in the Indo-Pacific.

India’s Hesitancy

As far as India is concerned, its diplomats and statesmen remained, for many years, ambivalent about the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept; apprehensive about the adverse reaction an overt show of support to this paradigm may evoke from China and Russia. The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) also worried that this vast geographic expanse would defy common policy-perspectives, and stretch its diplomatic resources. This ensured that India’s policy statements, related to this issue remained non-committal and anodyne.

The Indian Navy (IN), on the other hand, guided by a prime tenet of its Maritime Strategy—Shaping a Favourable Maritime Environment—has been actively reaching out to Indo-Pacific navies, and conducting ‘maritime diplomacy,’ via port-visits, naval exercises, disaster relief and refugee-evacuation operations.

Eventually, it seems that the reality of vital trade and energy sea-lanes that run across this region, combined with the imperative of reigning-in a hegemonic China, convinced the MEA of the Indo-Pacific logic. Consequently, in 2019, the MEA created separate divisions with a dedicated focus on the Indo-Pacific as well as Oceania regions. India also, formally went on record to define its perception of the Indo-Pacific as the ‘maritime space stretching from the western coast of North America to the eastern shores of Africa.’

A Prophet Ignored

Had we paid adequate attention to India’s ‘oracle of maritime wisdom’, Sardar KM Panikkar, we may have been better prepared for coming events. As far back as 1945, Panikkar had written: “While to other countries, the Indian Ocean is only one of the important oceanic areas, to India it is the vital sea. Her lifelines are concentrated here…her future is dependent on the freedom of this vast ocean.”

Panikkar had also forewarned us: “That China intends to embark on a policy of large- scale naval expansion is clear enough… with her bases extending as far south as Hainan, China will be in an advantageous position…” Panikkar’s prophesy came true, half a century later, in 2000, when China started construction of its southern-most naval base at Yulin, on Hainan Island.

Against this backdrop, let us take a look at the geo-political rationale underpinning China’s grand strategy, which seeks economic, political and military dominance right across the Indo-Pacific. The ‘Chinese characteristics’ of this strategy are symbolized by the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI); in which the ‘Belt’ refers to Chinese ambitions on land and the ‘Road,’ to the ‘Maritime Silk Road,’ its seaward component.

China Learns from Mackinder & Mahan

The BRI logic seems to be rooted in a proposition put forth by English geographer Halford Mackinder’s in 1904. Mackinder, known as the ‘father of geopolitics’ had pronounced that the 400-year era of sea power, was over, and the future of global power lay in control of the vast landmass of ‘Eurasia’ which he called the ‘World Island’. Mackinder marshalled geopolitics to argue that “he who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

In Mackinder’s day, Eurasia was dominated by Imperial Russia, but today, it is China, which is integrating Asia with Europe, through its internal network of high-speed railways, energy pipelines and fibre-optic cables. Having followed Mackinder’s prescription on land, China has also learnt from Admiral Mahan’s wisdom; as evident from the ambitious Maritime Silk Road with its huge economic and security implications, cutting a swath across the Indo-Pacific, and penetrating Africa.

Maritime power, has been deemed vital, by China’s leadership, not only, for protection against foreign hegemony, but also as a potent instrument for attainment of political goals. China’s grand-strategy is, therefore, underpinned by a huge build-up of maritime power—comprising a merchant fleet, a coast-guard, a maritime-militia, a fishing fleet and a shipbuilding industry. Each of these elements of maritime power, created by China, are the biggest in the world.

The Indian Scenario

Let us, now, consider, briefly, the current Indian scenario. India’s border problems, on land, go back to the 1950s when it acquiesced to China’s annexation of Tibet, which made it a contiguous neighbour, with a 4000-km-long border. The 1962 Sino-Indian War resolved nothing and created the anomaly of the so-called ‘line of actual control,’ (LAC) instead of a mutually agreed boundary. After relative calm for many decades, the past few years have seen a progressive rise in Chinese belligerence along the LAC; culminating in the April 2020 attempt to unilaterally alter the status quo through massive military deployment.

A decade earlier, China had announced its revanchist agenda via the ‘nine-dash line’ in the South China Sea. Having weathered the COVIDS-19 pandemic with relatively little economic impact, it has reaffirmed this agenda by its actions in the East and South China Sea, and the Indian Ocean as well as in the Himalayas. An economically strong, expansionist, and militaristic state, China will use the ambitious BRI, expand its sphere of influence via ‘debt diplomacy,’ and thereby establish dominance over the Indo-Pacific.

For the Indian Navy, there is considerable irony in the fact that it has taken the recent Sino-Indian border confrontation in the Himalayas, to bring political and public focus on the maritime domain. This irony is compounded by the fact that warnings by Admirals and analysts, about the steady growth of China’s maritime power and its hegemonic intent in the Indian Ocean, went unheard in the corridors of power, for over a decade.

It is, now, clear that in spite of the military asymmetry between China and India, and the active China-Pakistan nexus, Indian forces are well-placed to counter any localized offensive by one or both. However, there is also the stark reality that if full-scale hostilities break out, the best that India can hope to achieve, is a military stalemate on its northern and western borders.

Under these circumstances, as India prepares for the long-haul, it must bring to bear, all elements of its comprehensive national power against adversaries. That is the reason why attention has been focused on the maritime domain, where it is believed that India has some options, other than ‘boots on the ground,’ which could reinforce its bargaining position.

India’s Maritime Stakes

The waters of the Indian Ocean see over 120,000 merchantmen in transit, annually; carrying cargo worth a trillion dollars. These vessels also carry 95 percent of India’s vital seaborne trade—most of it by foreign-flagged ships. This renders our national growth and prosperity, dependent on the safety and security of international shipping which traverses these sea-lanes.

New Delhi’s ‘Look East’ and ‘Act East’ policies have seen India establishing close rapport with the ASEAN as well as other Pacific nations. While, over 50 percent of India’s trade with the greater Asia-Pacific transits through the South China Sea, Indian companies have acquired offshore and onshore hydrocarbon drilling rights in its littoral states as well as in the Russian Far East. India’s trading-links, investment and large diaspora, now span an arc extending from Siberia in the East to Central Asia, Africa in the West.

Any attempts to dominate the waters of the Indian or Pacific Oceans would, thus, represent a grave threat to India’s vital interests. In this scenario, what options does the maritime domain have to offer?

Maritime Options

An obvious course, for India, is to use the maritime domain for creating a more equitable balance of power vis-à-vis China. This could be done by employing two closely related maritime templates; the naval exercise ‘Malabar’ and the ‘Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’ or Quad—both with a common membership.

So far, members of the Quad have been circumspect about taking a firm stand vis-à-vis China’s aggressive conduct, but patience seems to be running out. Japan’s July 2021 defence White Paper opens with this statement: “China has continued its unilateral attempts to change the status quo in the East and South China Seas. China Coast Guard vessels are sighted almost daily… the raising of tensions in sea areas is completely unacceptable.”

Taking its cue from Japan, India must rally this quartet of democracies—so far, undecided—and motivate them to form a concert for ensuring a ‘rules-based order’ in Asia and the Indo-Pacific.

In terms of direct naval action, India has the option of employing conventional ‘naval deterrence,’ to dissuade China from pursuing its course(s) of action. As the world’s largest trading nation, China’s seaborne trade and energy imports constitute a vulnerable ‘jugular vein’. Regardless of buffer stocks, any disruption or delay of shipping traffic could upset China’s economy, with consequent effects on industry and morale of population.

Apart from its permanent military facility in Djibouti and the upcoming naval-base in Gwadar, China has created a series of ports in IOR littoral states, which could offer logistic support to its forward deployed forces. Thus, as the PLAN’s fleet strength grows, it would seek to create a permanent forward presence west of Malacca Strait, which would have the potential to pose a substantial threat to India’s shipping as well as its mainland.

The Indian Navy, in spite of fiscal constraints, has emerged as a compact but professional and competent force, and India’s fortuitous maritime geography will enable it to dominate the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. We must, however, bear in mind that China’s PLA Navy (PLAN) is underpinned by a powerful economy and supported by an efficient and prolific shipbuilding industry. Given the dismal state of India’s economy, impending warship retirements, and India’s tardy shipbuilding industry, the IN is unlikely to acquire significant force-levels augmentation in the foreseeable future. Therefore, as we reflect on India’s maritime security dilemmas, let us hark back to two historical events for some signposts for the future.

Borrowing a Garden Hose?

In 1941, when Allied nations—reeling under the German onslaught—sought US help, President Roosevelt signed the ‘Lend-Lease Act,’ under which the US ‘lent’ war materiel, including warships, tanks and aircraft, to the UK, France, China and even the Soviet Union. In return, the US received leases on naval bases during the war. Roosevelt explained it thus: “Suppose my neighbour’s home catches fire, and I have a garden hose… if he can borrow my hose… it may help him put out the fire.”

In my opinion, this would be a good time, for India to borrow a ‘garden hose’ from the US, or other friends, in order to pre-empt a conflagration in the Indo-Pacific, which could engulf the region. This would be a most befitting demonstration of India’s ‘strategic autonomy,’ in supreme national interest; and, here, a second historical event would serve to substantiate this.

In August 1971, in a major deviation from its policy of non-alignment, India signed the 20-year Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation, specifying ‘mutual strategic cooperation’. This alliance sent a strong signal to Washington as well as Beijing, to remain ‘hands off,’ and was a crucial factor in India’s 1971 victory. The treaty was renewed for another 20 years in 1991, and replaced by a 20-year Treaty of Indo-Russian Friendship and Cooperation in 1993.

The signing of the fourth and last of four ‘foundational agreements’, between India and the US, in October 2020, after 18 years of tortuous negotiations, removed a major impediment in the military relationship. There exist, now, an immense potential for Indo-US security cooperation at the strategic level, not just in the context of an immediate threat from an expansionist China, but for the long-term future.

History shows that neither appeasement, nor empty rhetoric has deterred hegemonic powers. India has, with considerable exertion and at substantial expense, stabilized the military situation in eastern Ladakh for the time being. But we face an adversary who is ruthless, ambitious and unpredictable.

If our diplomats and soldiers can succeed in gaining a breathing spell, in which to re-build our economic and military strength, we must use it to craft a cooperative strategy for a peaceful and stable Indo-Pacific, guided by civilized norms and respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty of all states. India as a democracy, a nuclear weapon state and a significant economic and military power, has no choice, but to stand firm; as a bulwark against hegemony in the Indo-Pacific.

-The author is a retired Navy Chief. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda