Sustainable development has become the key to the survival of the planet as the effects of global environmental degradation are becoming increasingly visible. The unchecked depredation of nature has also spread to the oceans and has given rise to the term ‘Blue Economy’. This first came to global notice when the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) pressed for the recognition of the oceans as integral to the future of a sustainable and equitable development model for mankind at the United Nation’s Rio+20 Conference in 2012.

The World Bank has defined the Blue Economy as the “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem.”

Balancing developmental imperatives with a sustainable model of economic growth across a wide spectrum of sectors related to the marine environment ranging from fishing to transportation, resource extraction, marine tourism to tapping the oceans for alternate sources of energy is going to be critical. The oceans cover 72 per cent of the surface of our planet and constitute more than 95 per cent of the bio-sphere. They sustain the essential ingredients that support life on earth and often provide the balance to sustain it. They are a source of food for large sections of global population and carry 80 per cent of global trade.

They are also a major source of hydrocarbons which meet the requirements of a developing world’s insatiable need for energy besides the potential for alternate sources of ‘blue’ energy. Human endeavour however is placing a huge burden on this precious resource which has the potential to meet the sustainable development needs of mankind but only if nurtured carefully.

Item No 14 of the Sustainable Development Goals enunciated at the Paris Conference in 2015 has highlighted the challenge posed by the phenomenon of climate change. The rapid melting of glaciers is disturbing the delicate eco-balance of the global oceanic spaces leading to higher sea levels which are threatening not only the livelihood of coastal communities across the world but even their very existence with countries facing the possibility of large scale inundation.

This vulnerability to coastal degradation brings with it numerous security challenges, both external and internal. As livelihoods are threatened and communities get marginalised, they become susceptible to ideological radicalisation and fall easy prey to disruptive forces as we are seeing happen in large parts of the world; this is exploited by extra regional powers who encourage destabilisation of economies through insurgencies to further their own national interests.

The increasing incidences of natural disasters, which are on the rise greatly, impact the security dynamics. Large scale destruction of life and property put further strain on economically challenged governments with limited resources; the political leadership is often found wanting. This encourages inimical elements within and outside the country to exploit and prey on the insecurities, fears and dissatisfaction of the people. Phenomena like piracy, maritime terrorism, and illegal immigration are all manifestations of this.

Closer home, the shift in the geopolitical centre of gravity to the Indo-Pacific in the last two decades has also brought with it numerous security challenges in this large oceanic space which is home to many large and small coastal and archipelagic states. These countries are wholly dependent on the sea for their livelihood, economic sustenance and their security.

India, the Indian Ocean and the Blue Economy

India, despite its peninsular conformation, is essentially a maritime nation with its 7516 km long coastline, an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in excess of 2.1 million sq km which is likely to increase to over three million sq km EEZ, if one were to include the continental shelf demarcation (which is almost as much as the landmass in area) and extremely rich in yet un-tapped resources.. It has two strategically located island chains comprising over a thousand inhabited and uninhabited islands – the Andaman and Nicobar Islands on the eastern seaboard and the Lakshadweep group of islands on the western seaboard. These are equally strength and vulnerable while being a vital asset of the national security construct.

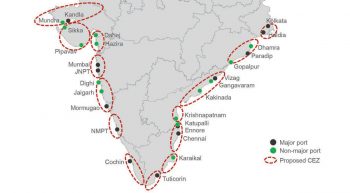

India has a substantial maritime infrastructure with 13 major ports and almost 200 non-major ports. It has a large mercantile fleet and more than 90 per cent of its trade by volume and over 75 per cent by value travels over the sea. It has a large coastal community with a substantial dependence on the sea for their livelihood as well as economic well-being and contributes substantially to the Indian economy. More than 80 per cent of India’s energy requirements whether indigenous or imported are met from the sea. The sea is therefore central to India’s energy security and the country therefore has to guard against any threat to the security of its energy requirements.

With the depletion in land resources and increasing urbanisation, nations are turning to the oceans to meet their burgeoning demands. This will inevitably give rise to competition, confrontation and possible conflict. The portents of this are already quite visible as emerging regional powers are challenging the traditional maritime boundaries and changing the geopolitical contours of the region itself. This challenge to the status quo is further exacerbated by the presence of large extra-regional powers in the region and their strategic imperatives.

India has mandated itself as a net security provider in the Indian Ocean which places on it a great responsibility. As the leading Indian Ocean power, India must develop a long term vision with a synergistic economic, security and political approach to leverage its strengths and develop a collective and inclusive Blue Economy agenda for the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and use this collective strength to drive the global agenda for a sustainable future for mankind. This will require a combination of economic strength, deft diplomacy, a secure environment and a political will where the whole will be greater than the sum of its parts.

Since 2014 when the current government assumed office, India’s largely continental mindset has seen a subtle shift towards a maritime orientation. During his visit to Mauritius in March 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to the Blue Chakra or wheel in India’s national flag as representative of the potential of the Blue Revolution in the Blue Economy. Two important and transformational maritime initiatives called Sagarmala and SAGAR, an acronym for Security and Growth for All in the Region, have been implemented which highlight this shift.

Sagarmala is a port development led programme to augment and rejuvenate India’s maritime infrastructure and maritime transportation, including inland waterways towards utilising India’s substantial natural and man-made maritime assets to optimise our economic potential.

SAGAR envisages a collective approach to the security and economic well-being of the region. Both these initiatives, if properly coordinated and effectively implemented can complement each other towards harnessing India’s enormous marine potential for creating a secure maritime environment in the region as well as its economic enhancement in a sustainable framework in keeping with the principles of Blue Economy.

Maritime security and the Blue Economy are closely interlinked. The exponential increase in the trans-national maritime security challenge has led to nations re-orienting their security architecture to address these threats. Most of these are directly related to the development deficit in coastal communities, the effects of climate change, natural disasters and human disregard of the marine eco-system either due to ignorance or plain callousness. This new security paradigm therefore requires a comprehensive and cooperative approach as the very fabric of the global commons being equal to all mankind stands threatened. The cost of countering these threats further strains the economy and is often at the cost of social development. For over a decade the piracy in Somali waters and the Horn of Africa has led to a huge multinational naval presence to protect the sea lines of communication and shipping with large destroyers and frigates deployed to counter illiterate gun-toting youth in small skiffs. The cost of this effort has been totally disproportionate to the threat if viewed in its entirety.

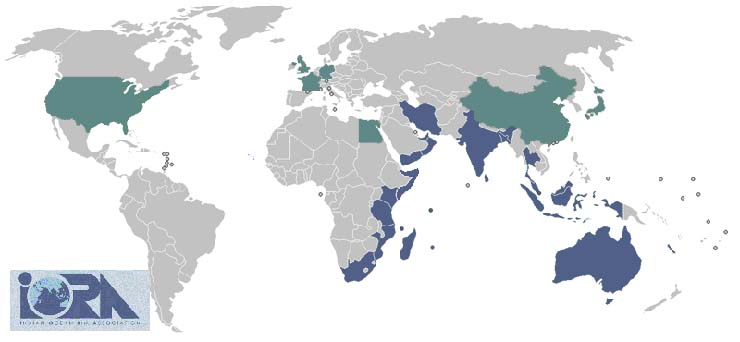

Besides the conventional and sub-conventional security challenges, non-traditional security threats have created their own dynamic. Natural calamities and man-made disasters are on the rise – the effects of humankind’s assault on nature – leading to untold misery to coastal communities across the region and indeed the world. Addressing these first requires a global acknowledgement of the magnitude of the threat and the need to think and act beyond physical and mental geographies. Unfortunately, some of the biggest perpetrators of this are in a state of denial, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Notwithstanding these aberrations, a focussed multi-lateral and multi-layered dynamic approach by global and regional institutions, individual governments, global and local industry, non-governmental organisations, community outreach programmes and many such initiatives can offer a way ahead. Initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are at least generating a discussion and some action which is a good beginning. Nearer home, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) has included sustainable development in its agenda and it has been the topic of discussion at numerous maritime conferences in the region. It is mechanisms such as these coupled with smaller regional groupings like BIMSTEC, SAARC, EAS and executive level groups like the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) which India needs to leverage to take leadership in the Blue Economy initiatives in the region.

India’s capacity constraints and bureaucratic apathy have made it vulnerable to an aggressive extra-regional presence in the neighbourhood. Traditional friends and allies in our ‘strategic backyard’ are being seduced by economic largesse into committing themselves to long term economic dependence on extra-regional powers which has grave economic and security consequences for India and is detrimental to the collective economic security of the region. India will therefore have to develop adequate ‘Blue Muscle’, to support its Blue Economy initiatives (which now extended much beyond just trade) and shape the environment on terms favourable to India.

The Indian Navy and the Coast Guard are on a growth trajectory towards a balanced full spectrum capability but this is being stymied by budgetary constraints and bureaucratic inertia thus leading to critical capability deficits in the national maritime security construct. Both, capacity and capability need careful attention.

Suggested Way Ahead

India, as the largest maritime power in the Indian Ocean has to be at the forefront in promoting Blue Economy initiatives in the region. Capacity building and capability enhancement in a cooperative and inclusive framework will go a long way in gaining the confidence of the small island states and nations with large coastal communities who lack the potential, capacity and size to matter on the world stage. The support of these nations in global and regional institutions will help leverage the Indian perspective towards our larger international ambitions as a global force for good. However, for that we need to first ensure that internally, we have a comprehensive, coherent and cohesive approach towards the maritime domain and appreciate its criticality to India’s strategic ambitions. For many years now, the need for an empowered maritime body is being articulated but has yet to find favour with the political leadership for reasons not understood. Presently, maritime- related affairs of the country are represented by a multitude of ministries and departments at the Centre and in the States more than 25 ministries and departments with its deleterious effects on a consensual approach or effective decision making. The need of the hour therefore is to have an empowered Maritime Adviser to the Government of India working directly under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and assisted by governmental and non-governmental domain experts representing the full spectrum of maritime activity to develop an actionable time bound way ahead with adequate budgetary support.

Sagarmala and SAGAR have the potential to change the Indian maritime landscape and must therefore progress in a time bound manner with resources being optimally utilised towards efficient implementation. The augmentation of the maritime infrastructure should also be extended to neighbouring countries on a mutually complementary basis. Induction of global technology and best practices should be encouraged by providing an enabling policy and regulatory framework to encourage foreign investment.

Revitalise the country’s shipbuilding industry by incentivising shipyards to become globally competitive by subsidising shipbuilding and offering investment funds at competitive rates of interest.

There is enough evidence to suggest that the recent maritime resurgence in the region through various schemes like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is all related to the Blue Economy. The belligerence of some extra-regional powers to seize the initiative in tapping the abundance of marine resources and developing the maritime infrastructure in the region abundantly clear. This is creating economic and security dependencies which can lead to further exploitation and consequent de-stabilisation of the region which will be detrimental to India’s and the region’s collective national interest.

India, as the pre-eminent power in the region must retain its advantage through a multi-dimensional and multi-sectoral approach. Maritime security against trans-national and non-conventional threats being integral to it. Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) and capacity building in this area through a robust information sharing mechanism, training programmes, bilateral and multilateral exchanges and exercises, interoperability, support in augmenting force levels and technologies, and providing Maritime Domain Awareness to counter threats are some of the areas which would generate a non-threatening environment of mutual trust and confidence.

Conclusion

The subject of the Blue Economy needs to be understood in its entirety by the policy makers as it is going to witness an exponential increase in importance as a model for sustainable development in the future. The fragmented maritime decision making apparatus in the government comprising numerous ministries and departments needs to be overhauled and placed under an empowered authority with multi-sectoral representation comprising domain experts who will report directly to the Prime Minister.

(Commodore Anil Jai Singh is a veteran submariner with over three decades service in the Indian Navy. He is now the Vice President of the Indian Maritime Foundation. The views expressed are personal.)