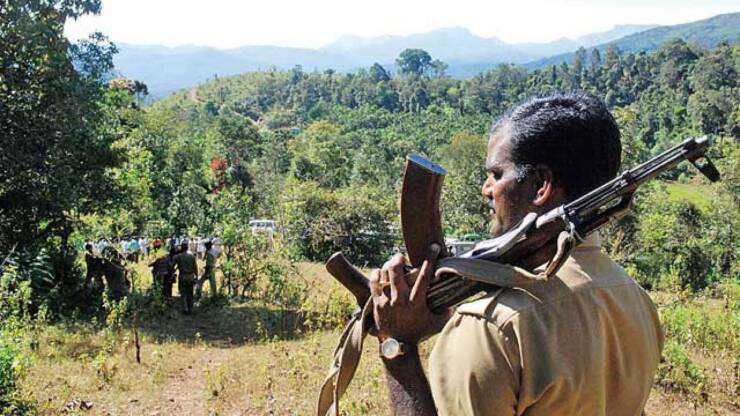

India has been waging a war against Maoist violence, also known as Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), for over five decades now. The latest attack in Sukma district of Chhattisgarh on April 3 claimed the lives of 22 jawans from the state police and the CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force); another 32 security personnel were injured in the Naxal ambush.

As the post-incident analysis and finger-pointing continues among security experts, intellectuals, and in the media, a recently-published paper on the subject of “Intellectuals and the Maoists” by Uddipan Mukherjee explains in great detail and clarity the issues surrounding Left-Wing Extremism. Incidentally, LWE has been described by the government as the biggest threat to India’s internal security.

Given the current discourse on “Urban Naxals/Maoists”, this is a very timely essay as Mukherjee delves into the concept of ‘intellectuals’ and their role in India’s Maoist insurgency. Some of the questions he attempts to address in the discourse on Maoist intellectuals are not only relevant but also quite fascinating. For example, in his own words:

“Are the intellectuals always anti-state? Can they bring about a revolution or social change? What did Gramsci, Lenin or Mao opine about intellectuals? Is the ongoing Leftwing Extremism aka Maoist insurgency in India guided by intellectuals? Do academics, students, writers, journalists, film-makers, actors and poets, within India and without, in any way provide a fillip to the movement? Is there any ecosystem that binds the intellectuals and the insurgents together? Are the counter-insurgent Police well within their mandate to nab ‘intellectuals’ in the urban landscape, allegedly as supporters of the Maoist movement? How is the future trajectory shaping up in this contest between the state, intellectuals and the insurgents?”

Before he sets out to answer these questions, Mukherjee highlights the changing role and tactics of the Indian police in counterinsurgency operations against the Maoists.

For Example: “In November 2019, Police in India’s southern state of

Kerala arrested two activists of the mainstream leftist political party – Communist Party of India – Marxist (CPI-M). They were booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act [UAPA] due to their alleged links with the banned Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist). Incidentally, one of the activists, Alan Suhaib, was a law student… Does the Kerala wing of the CPI-M harbour or even encourage the ultra-leftist viewpoints within the party? Or was this a failure of the local party leadership to curb the growth of such radical views? Or is it a mere aberration, the adventurism of two young party activists who were still in their formative stages of ‘ideology’?

“Notwithstanding the responses to these questions, one aspect is clear as crystal – educated youth can somehow get attracted toward extremist viewpoints.

“Why?

“Is it romanticism? Is it a youthful predilection? Is it pure ‘josh’?

“In November 2019 itself, Police in the Bastar District of Chhattisgarh arrested a Professor of Delhi University and another academic of the Jawarharlal Nehru University, along with a few Maoists, in connection with the murder of a tribal villager in the LWE affected Sukma district of Chhattisgarh. One of the professors was Nandini Sundar, writer on tribal anthropology and the activist who spearheaded the Public Interest Litigation [PIL] in the Supreme Court leading to the quashing of the vigilante movement, Salwa Judum.

“Interestingly, in the happening month of November 2019, the Pune Police searched the Noida home of an Associate Professor of Delhi University in connection with a 2017 case where ten activists had been imprisoned for more than a year while on trial for alleged Maoist links. Barely a month before this string of incidents, in October 2019, an Assistant Professor of the Hyderabad-based Osmania University was arrested for suspected links with the banned Maoists. The academician K. Jagan, was also a member of Viplava Rachayitula Sangham, a revolutionary writers’ association – and possible front organisation of the Maoists.

“Going back in time, in 2017, the Maharashtra Police felt vindicated when the Maoists put up posters in support of the Delhi University Professor G.N. Saibaba, who was arrested and subsequently convicted for alleged links with the communist ultras.”

The above incidents cited by Mukherjee pertain to police action in the past four-five years against “urban Naxals” and “overground supporters” of the Maoists in India. He then goes on to trace the early concepts “ideology”, “intellectual” and “revolution” by citing examples and writings of western Marxists, philosophers, and intellectuals.

Western Influence

“Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci… continued to research the question ‘who is an intellectual’ among an array of administrators, scholars, scientists, theorists and philosophers. According to Gramsci, all men are intellectuals, but not all men serve the function of intellectuals in society…”

The Maoist doctrine was endorsed in varying measure by a stream of French intellectuals, writes Mukherjee, quoting Richard Wolin: “Suddenly and unexpectedly, Maoism had acquired immense cachet as political chic. It began attracting prominent intellectuals—Michel Foucault as well as Tel Quel luminaries Philippe Sollers and Julia Kristeva—who perceived in Maoism a creative solution to France’s excruciating political immobilism.

“In All Said and Done, Simone de Beauvoir, notes: “Despite several reservations – especially, my lack of blind faith in Mao’s China – I sympathize with the Maoists. They present themselves as revolutionary socialists.”

Mukherjee cites popular philosopher and writer Jean-Paul Sartre as an advocate of social engagement and an active supporter of varied causes such as the Algerian, Cuban and Vietnamese revolutions.

“Sartre even wrote the introduction to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, where he endorsed revolutionary violence as a liberating force in the face of the violence of the ruling regime. Sartre, however, avoided any direct commitment to parties that espouse these revolutionary ideas…

“The father of post-modernism, Michel Foucault… argued that it is clear that we live under a dictatorial class regime, under a class power that imposes itself with violence, even when the instruments of this violence are institutional and constitutional. When the proletariat triumphs, it will also exert a power that is violent, dictatorial, and even bloody, over the class it has supplanted. While agreeing with the fact that the existing court system manifests the interests of the ruling classes, Foucault rather amusingly opposed the creation of people’s courts on the basis of proletarian class interests.

“Many of the French intellectuals who became infatuated with Maoism in the 1960s would eventually end the dalliance due to several factors. The death of Mao in 1976, the capitalist upsurge in post-Mao China as well as the fall of Soviet Communism, led many ‘bourgeois intellectuals’ to veer away from the path of revolutionary change. Moreover, Postmodernism became the new craze as many of these very same intellectuals, who were poster boys of Maoism, started sternly criticising the concepts of class analysis, the party, the dictatorship of the proletariat, and Marxist theory on the whole.”

Indian ‘Intellectuals’

Mukhherjee contrasts this with the scenario prevailing in India:

“The government of Karnataka had prepared a list of college teachers, newspaper editors and some NGOs purportedly ideologically close to the Naxals [Maoists]. A group of these intellectuals, arrested in 2003, included the likes of actor-director-playwright Girish Karnad, winner of a slew of national awards, including the Padma Bhushan. Karnad had also served as Chairman of the national Sangeet Natak Academy and President of the Karnataka Nataka Academy, both Government backed institutions. Apart from Karnad, the list included Professor Govind Rao, Dr Sridhar and others, who were incarcerated in 2003 when they had participated in a rally in support of the Supreme Court decision with regard to a Sufi shrine.

“Binayak Sen is another case in point. He was arrested by the Indian Police for alleged links with the Maoists. At the other end, he was nominated for the Gandhi Peace Award in 2011 by the Gandhi Foundation – an organisation based in London that could safely be construed to be driven by intellectuals…

“Interestingly, most Indians know Dr. Sen through the media, and their opinion about him, his family and other activists spread around the Maoist heartland, was shaped by news articles, both in the national as well as in international circuits. At the time of the Gandhi Peace Award, Dr. Sen was yet to be totally absolved of the charges of sedition. An award for him in the international arena at that juncture could have created a mess for the Indian judiciary. Sen, however, voluntarily relinquished the award.

“The award for Dr. Sen was surely a decision taken by a coterie of sociologists, anthropologists and activists. It did not reflect the ‘will’ of the autochthonous Adivasis, and the conferment of the award did not elevate Dr. Sen to the position of a ‘messiah’ of the Adivasis. Yet, such a move by the Gandhi Foundation surely elevated the ‘intellectual’ Sen to a pedestal of infallibility even while he was facing serious criminal charges.

“That, in turn, may have encouraged other ‘intellectuals’ to collude with the Maoists, as a pathway to attain cult status as ‘celebrity (read seditious) rebels’ against the state.

“Film-maker Aparna Sen, dramatist Shaonli Mitra, poet Joy Goswami and others were arrested by the Police while entering Lalgarh, the epicentre of the 2009 crisis in West Bengal. Police reports submitted to the government suggested that some of the Maoists had accompanied the intellectuals during their Lalgarh trip. When the intellectuals were questioned about this nexus, they expressed total ignorance.”

Radicalising Effect

Mukherjee then swiftly goes back to the 18th century to an important milestone in history:

“On the global platform, the phenomenal French Revolution did not occur in an intellectual vacuum. Voltaire, Diderot, Montesquieu and Rousseau drove the intellectual revolution, years before the actual physical revolution took place. Rousseau’s concepts of ‘sovereignty’ and ‘general will’ played a substantial role in radicalising the movement. That was the 18th century.

Mukherjee then cites the examples of some of India’s well-known left-leaning “intellectuals” and their streams of thoughts during the last five decades.

“The submission of the doyen of subaltern historiography Ranajit Guha, is startling. In an interview, Guha emphatically says: “Later, I became something of a Naxal intellectual. I still consider myself to have been inspired by Charu

Mazumdar’s ideas, which I think contain a lot of validity. But Charu Mazumdar and his followers were weak in organizational capability, which resulted in the movement being crushed. I have elsewhere condemned the role of some intellectuals in Indira Gandhi’s period who supported her moves to crush the revolt…

“Guha points toward various kinds of intellectuals; one set of intellectuals who ‘oppose’ the state (to which Guha belongs in this case) and another set which aligns with the state in order to obliterate the former – in a war of ideology, ego and power.

“It has however become quite a fashion for a bulk of the intellectuals in today’s India to criticise government policies and programmes. In a sense, criticising the government seems to be a criterion for being qualified to be an intellectual. India today needs what Gramsci termed as “organic intellectuals” — committed to the cause of the people.

The Naxalbari Spark

The author then recalls the genesis of India’s Naxalites aka Maoists. About how it all started in March 1967 when a young share-cropper, Bigul Kisan, in the Naxalbari area of the northern part of West Bengal, was attacked by armed goons of the local jotedar when he had gone to till the land, in possession of a judicial order empowering him to do so. What followed was an armed struggle in which the oppression by the landlord-bourgeoisie nexus was bludgeoned by a unified band of tribal-peasants, invigorated by the fiery speeches of the ideologue of class-annihilation – Charu Mazumdar.

“Since then, the movement has seen several ups and downs, bitter internecine showdowns, severe state repressions as well as splits, mergers and a mega-merger in 2004. But, the central theme of the Naxalites [derived from ‘Naxalbari’] has remained almost the same. They have viewed independent

India as a multi-national country and supported the right of nationalities to self-determination, including secession.”

“Moreover, they have clearly stated that the ruling bourgeoisie is comprador, Indian independence was fake, and that India has a semi-colonial and semi-feudal status. Thus, in order to establish a people’s government in India, Mao

Zedong’s guerilla warfare tactics have to be employed and a protracted armed agrarian revolution is the only feasible solution in this regard.”

Mukherjee puts the Indian Naxalite/Maoist movement in perspective by pointing to the decade of upheaval across the globe and how much of an impact those global events had on Indian intellectuals and revolutionaries.

“The late 1960s, and especially 1966 to 1968, were a period during which modern history boasts of a multiplicity of revolutionary movements, cutting across regions and continents. It was also a phase when student agitation gained unprecedented ground. Whether it was Berlin or Paris or Calcutta, the intellectual stimulus had engineered student movements – highly radicalised in thought and action. Blame it on the zealot-philosophers Frantz Fanon, Herbert Marcuse or Jean-Paul Sartre, to name a few!

“Fanon passed away due to leukemia in 1961, but before that his firebrand writing achieved cult status. In his monograph The Wretched of the Earth, he wrote, ‘…this same violence will be vindicated and appropriated when, taking history into their own hands, the colonized swarm into the forbidden cities.’

“Fanon believed that society had to be changed and could only be changed through violence, and violence was a personal cathartic – an individual could only find true expression and release in violence.

“The late 1960s were also a period of the rise of the ‘New Left’. Herbert Marcuse believed that man in Western capitalist society was every bit as enslaved as his counterpart in the totalitarian societies of the Soviet bloc. The New Left rejected both western capitalism and Soviet-bred communism. According to the New Left, the state maintained a dominant class interest through violence, psychological as well as physical. Hence, it was ‘just’ to use violence against the state as an instrument of emancipation.

“Violence was also projected to be glamorous and, in the post-1967 world, Peter Reed opines, rugged good looks and violence came together in the ideal poster: Che Guevara.

“Heroic failure was more potent than success. 1967 was an eventful year – the death of a student in Berlin in a fracas with the Police, which later on assumed deadly proportions in the rise of the Baader-Meinhoff gang and its series of abductions and high-jackings, the death of Che Guevara in a Bolivian ravine, and finally the commencement of the historic Naxalbari uprising in India’s eastern province of West Bengal.”

Cult Posterboys

Mukherjee says Naxalbari quickly came to enjoy an iconic status among Indian revolutionaries. ‘Naxalite’ became shorthand for ‘revolutionary’, a term which evoked romance and enchantment at one end of the political spectrum and distaste and derision at the other.

“Charu Mazumdar was a frail heart patient. However, he emulated the likes of Mao, Guevara, Castro and perhaps Cambodian dictator Pol Pot, as he unleashed his ‘Eight Documents’. He attempted to justify the use of violence against the Indian state by positing his ‘Theory of Annihilation’ of class enemies.

“Calcutta’s Presidency College and Jadavpur University spilled over into the rural backyards of Bengal to ‘spread’ the revolution… violence was the fuel – driving the engine of revolution.

“The class enemy was not clearly defined, but the ‘annihilation’ campaign was on – which was sometimes grotesquely evidenced in the form of ‘police-wallahs’ being murdered in broad daylight, often while not on duty and unarmed…

Mukherjee notes that the “annihilation of usurious landlords through small squad actions, operations which were bloated to be termed as guerrilla warfare, were carried out with impunity – with the fervent hope that such numerous and gory actions would definitely ignite the revolutionary consciousness of the masses.”

“On the contrary, such dissolute actions by the Naxalites only hastened their loss of connectivity with the people and paved the way for their eventual defeat in the first phase of the movement and triggered the dismemberment of the party – along the pro-mass line and the pro-annihilation line. The chief architect of the Annihilation Theory, Mazumdar was finally arrested by the Calcutta Police on July 16, 1972, and lived only 12 days after his arrest.

“Was indiscriminate use of violence the fundamental cause of the demise of the romantic revolutionary vision? Indubitably, it was one among others, if not the primary reason.”

“The debacle of the Naxalites, however, was critically rooted in their lack of armed preparedness and the imperfect development of the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army [PLGA]…”

(Continued in Part 2: Maoists & Urban Naxals — Why India Needs to Dismantle This Internal Security Threat)

-Ramesh S. is a senior journalist and Consulting Editor with Raksha Anirveda

[The article is an adapted version of the research paper ‘Intellectuals and Maoists’ that was featured in Faultlines, a quarterly published by the Institute for Conflict Management. Its author, Dr. Uddipan Mukherjee is an IOFS officer and currently serving as Joint Director & PRO – Ordnance Factory Board, under Ministry of Defence, Government of India. He was part of a national Task Force on Left Wing Extremism set up by the think tank VIF. The views expressed in this paper are his own and not of Government of India / Raksha Anirveda.]