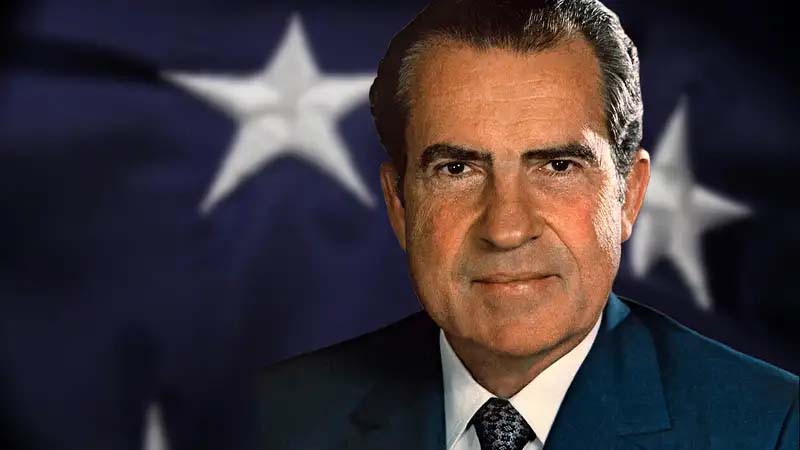

During the 1971 War, as the Indian Army launched its blitzkrieg to liberate East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) – where the Pakistan Army had committed the genocide of 3 million citizens and raped at least 200,000 women – US President Richard Nixon had a terrible idea. Under the pretext of evacuating American citizens from the warzone and prodded by his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, Nixon ordered the US Seventh Fleet’s Task Force 74, led by the nuclear powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, to proceed towards the Bay of Bengal.

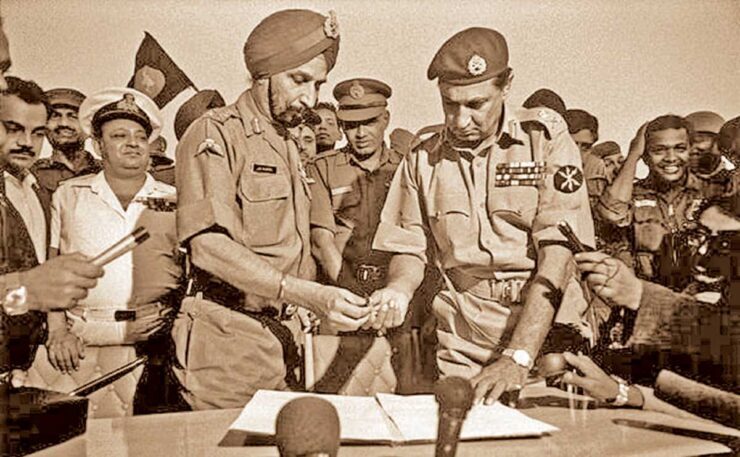

Nixon’s rash move – which became America’s greatest PR disaster in India – was dictated by the condition of the Pakistani military that was taking a hammering in East Pakistan. More than 100,000 Pakistani soldiers were trapped between the Bay of Bengal and the rampaging Indian Army. Of these 93,000 would soon surrender, making it the largest capitulation since World War II.

The Indian Army had not yet made any major attacks in the western sector, but a CIA mole in Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s cabinet had leaked her plan to bomb Pakistani military capability into the Stone Age. Hassan Abbas writes in Pakistan’s Drift into Extremism that “India’s plans possibly included the final destruction of the country, as a CIA report had indicated”.

Nixon – who was working to achieve a diplomatic breakthrough in China, with Pakistan acting as the middleman – asked Beijing to mobilise troops on the Indian border. He even contemplated “lobbing nuclear weapons” at the Russians if they retaliated by going to war with China. But after Moscow moved its crack army divisions to the Chinese border, Beijing decided it was not going to sacrifice itself at Nixon’s bidding. At any rate, China considered East Pakistan a lost cause.

A livid Nixon stressed he would not allow India to break up Pakistan’s core territories in the west. He warned the Indian ambassador LK Jha in Washington: “If the Indians continue their military operations (against West Pakistan), we must inevitably look toward a confrontation between the USSR and the US. The Soviet Union has a treaty with India; we have one with Pakistan.”

Not satisfied with the envoy’s reply, Nixon ordered the USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal.

Enterprise Heads For India

Former Indian Navy Commander Raghavendra Mishra, a research fellow at the New Delhi-based National Maritime Foundation, writes in a paper titled ‘Revisiting the 1971 USS Enterprise Incident’ that the nuclear powered, nuclear capable carrier’s entry was an instance of gunboat diplomacy.

In the paper, published by the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, he writes: “A broad plan of action emerged, which included cutting off economic aid to India, and transfer of military equipment from other US regional allies to West Pakistan. These were to be supported by a possible naval deployment and a simultaneous move by the Chinese military along the border. The aim was to put pressure on the Soviet Union which, in turn, would prevail upon India from expanding the conflict. Nixon directed Kissinger to explore the option of US naval deployment with Chinese representatives before taking a final decision.”

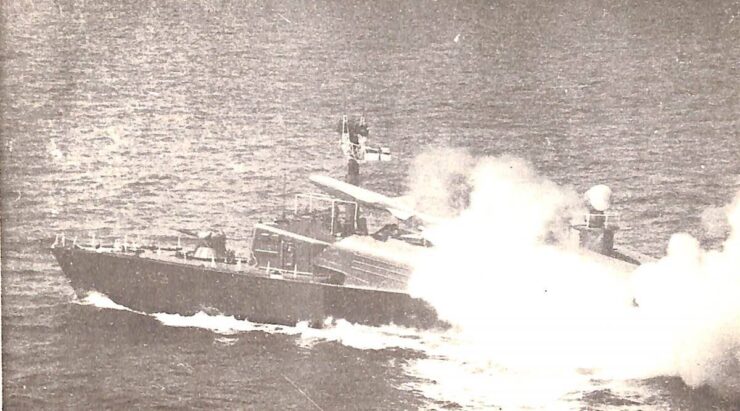

The first mention of an aircraft carrier deployment comes up in Kissinger’s memorandum to Nixon on December 8, 1971. That was the night when the Indian Navy had made a bonfire of Karachi, with its second successive missile strike on coastal installations. The Pakistani port had been burning since December 4 after being hit by the Indian Navy’s Russian missile boats. These strikes in the west plus news about the collapse of the Pakistan Army in the east had greatly upset the Nixon-Kissinger duo.

Kissinger suggested that Nixon should direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – the highest-ranking and senior most military officer in the United States armed forces – to move naval Task Force 74, then deployed in the South East Asian theatre, to the Bay of Bengal immediately via the Singapore Straits under the pretext of “prudent contingency measures”.

On December 9, Nixon wanted the US and China to jointly move against India. That same day, during his meeting with the Chinese delegation led by Huang Hua, China’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and Ambassador to Canada (as the US did not have diplomatic relations with China), Kissinger apprised his counterpart about the US naval task force move through a map showing the deployment of the US and Soviet forces.

Commander Mishra writes: “Kissinger agreed the Pakistani military had collapsed in the East and the same was anticipated within two weeks in the West. Emphasising the importance of West Pakistan’s continued existence for regional dynamics, Kissinger sought military moves by China along the border to restrain India and the Soviet Union. Huang Hua, while expressing solidarity for the common cause, made no formal commitment, stating that he would convey the US proposal for consideration of Beijing.”

By December 11 the carrier Task Force 74 led by the Enterprise was moving as scheduled and the first media reports about its possible deployment in the Bay of Bengal had started circulating in India.

On the same day, a major development took place. Around 4.00 pm, an Indian parachute brigade was dropped at Tangail and the race for Dhaka had begun. With the Pakistani military and political leadership in panic mode, Kissinger informed Pakistani Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto that Task Force 74 would be crossing the Straits of Malacca by December 12-13.

War In The East

A week into the war, it was clear the Pakistan Army in the East was about to capitulate. The Americans also realised to their dismay that China was not prepared to move even a column of trucks on the Himalayan border.

Overcome by his hatred, the reckless Nixon was even prepared to sacrifice the concept of détente that would soon be the cornerstone of US-Russia ties. He asked Kissinger to inform the Russians about the increasing probability of a major war involving both the superpowers. Moscow was told that its continued backing of New Delhi would endanger the planned Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT).

It is unclear whether Nixon’s threat worked or whether the Russian leadership was unduly sensitive about global opinion, but soon Russian ambassadorial staff informed Kissinger that a delegation from Moscow had arrived in New Delhi for consultations, and that India had agreed not to expand its military operations in the Western theatre.

During his meeting with Chou En-Lai in Beijing in February 1972, Nixon had said that in the early stages of the conflict the Russians “were doing nothing to discourage India in its actions against Pakistan. It was only after we made a very strong stand – I personally intervened with (Russian President Leonid) Brezhnev, and Dr Kissinger made a statement that was widely quoted in this respect – they took a more reasonable attitude and a more moderate position in the United Nations”.

Mishra adds: “At this stage, the US administration possessed reasonable proof that West Pakistan would not be attacked by India. However, in a meeting attended by senior state and defence department officials, Kissinger decided to go ahead with the naval deployment, which was expected to traverse the Straits of Malacca in the evening and could arrive off East Bangladesh on the morning of December 16.”

On December 13, Pakistan’s Ambassador to the US, General Raza, requested the US Seventh Fleet deployment in the Bay of Bengal as well as in the North Arabian Sea to deter further attacks by the Indian Navy. This proposal was repeated by the President of Pakistan to Nixon, stating: “The Seventh Fleet does not only have to come to our shores but also to relieve certain pressures which (we are) not in a position to cope with. (We) have sent a specific proposal…about the role the Seventh Fleet could play at Karachi which, I hope, is receiving your attention.”

(This excerpt from the conversation between Nixon and his assistants is from December 15, 1971, 8:45-11:30 am.)

Kissinger: The Russians came in yesterday giving us their own guarantee that there would be no attack on West Pakistan.

Nixon: A letter from Brezhnev.

Kissinger: An addition – an explanation of the letter to – of Brezhnev saying, they, the Soviet Union, “guarantees there will be no military action against West Pakistan”. So we are home, now it’s done. It’s just a question of what legal way we choose.

Nixon: Well, what the UN does is really irrelevant.

Kissinger: Well, it’d be, the bastards (he’s referring to Indians), of course, have broken promises before. It’d be better to have it on public record. We might be able to do it in an exchange of letters between Brezhnev and you. That is made public, in which you say you express your concern, and he says he wants to assure you.

Nixon: Well, what does that do now to the Chinese?

Kissinger: Oh, the Chinese would be thrilled if West Pakistan were guaranteed.

N-Standoff: Enter The Russian Navy

Based on an Indian intercept of US communications, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) prepared a six-page note, which said: “The assessment of our embassy reveals that the decision to brand India as an ‘aggressor’ and to send the 7th Fleet to the Bay of Bengal was taken personally by Nixon.”

The MEA felt that “the bomber force aboard the Enterprise had the US President’s authority to undertake bombing of Indian Army’s communications, if necessary”.

Following this assessment, India secretly activated a provision in the Indo-Soviet Friendship Treaty, according to which either party would come to the defence of the other. A Russian naval task force from the Pacific Fleet based in Vladivostok, consisting of a cruiser, a destroyer and two attack submarines, under the command of Admiral Vladimir Kruglyakov intercepted Task Force 74. Sebastien Roblin writes in War is Boring that Kruglyakov revealed in a Russian TV interview (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Er2E_PpVUYw) about “encircling” the task force, surfacing his submarines in front of the Enterprise, opening the missile tubes and “blocking” the American ships.

Mishra notes: “The Soviet Indian Ocean naval component also got a lucky break with three of their ships near the Straits of Malacca, on their return passage to their Pacific homeport when the information about the possible US naval deployment to the Indian Ocean became general knowledge. These were retained and reinforced by two further task groups that arrived in the Indian Ocean on December 18 and 26. These Soviet naval assets continued to shadow the TF 74 off Sri Lanka until its return passage to the Pacific theatre on January 8, 1972.”

In addition, 12 other Soviet naval ships were present in the Indian Ocean. However, none of these Russian vessels were in the vicinity or heading for the Bay of Bengal or North Arabian Sea, where the Indian Navy was continuing with its operations.

It is an indication of how serious the Russians were about defending India that Moscow started despatching naval detachments from across the globe to Indian waters. Kissinger referred to unconfirmed reports about Soviet Mediterranean Fleet units being directed to the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal, but these warships were unlikely to arrive in time.

The reason Russia was able to quickly direct all this heavy naval firepower into the warzone was the Soviet Navy had rapidly grown into an impressive Blue Water force under Admiral of the Fleet Sergei Gorshkov.

John B Hattendorf writes in ‘US Naval Strategy in the 1970s’ that the year 1970 was a seminal one as the Soviet Navy carried out the first of its OKEAN global war games that involved combined and joint forces for defensive, offensive and expeditionary operations. “The 200-ship exercise covered the four major theatres of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans as well as the Mediterranean Sea. This was also a period that the majority of the US Navy was approaching en masse obsolescence. The increase in Soviet naval presence was especially notable in the Indian Ocean, which far outstripped the US Navy deployments, although it is qualified that most of these deployments were in the North and South-West Indian Oceans.”

With such massive forces at its disposal, the Russian military forces were confident of repelling any American adventurism. Mishra says the Russian ambassador to India had dismissed the possibilities of the US or China intervening by emphasising that the Russian fleet was also in the Indian Ocean and would not allow the Seventh Fleet to interfere; and if China moved in Ladakh, Russia would respond in Xinjiang. As Nixon raged in the White House, a million Russian troops were stationed on the Chinese border.

At this point, Task Force 74 was east of Sri Lanka and this naval deployment had generated considerable anti-US feeling in India. Indian Foreign Minister Swaran Singh said that if the US invaded, the Indians would trap the Americans in a disaster greater than Vietnam.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani media was still publishing speculative reports about a possible naval intervention.

Nuclear Threat: Real Or Imagined?

There are military experts – both Indian and foreign – who deny the US had plans to launch military attacks, let alone a nuclear strike, on India. However, before second guessing Nixon’s intentions, let’s look at the components of Task Force 74. Commander Mishra lists the following:

- 1 Nuclear powered strike carrier – USS Enterprise, 90 aircraft

- 4 Gearing class destroyers

- 3 Missile destroyers

- 2 Amphibious assault ships with 2,000 Marines

- 1 Nitro class ammunition ship

- 1 Replenishment oiler

- 1 Nuclear attack submarine (SSN)

There are several reasons pointing to the seriousness of the threat. One, the availability of such potent assets was itself a temptation for the use of force by Nixon and Kissinger.

Secondly, both Kissinger and Nixon were consumed by an intolerable hatred towards India. The US President referred to Indians as “slippery, treacherous people”. Of Indira Gandhi, he was recorded as saying, “The old bitch. I don’t know why the hell anybody would reproduce in that damn country, but they do.” Ironically, Nixon was personally fond of Pakistani President Yahya Khan, who had massacred 3 million of his own Bengali citizens.

Kissinger also liked Yahya as he was the intermediary helping the Americans reach out to China. It was clearly a role the Pakistani dictator relished. “Yahya hasn’t had such fun since the last Hindu massacre!” Kissinger remarked.

Thirdly, Nixon and Kissinger were mired in the Vietnam War, which was proving to be a meat grinder for Americans troops. Massive US strategic bombing hadn’t broken the spirit of the Vietnamese but had in fact steeled their resolve to hit back harder. Because of this, Nixon’s popularity had plummeted at home. India had backed a number of UN resolutions condemning the US bombing of Vietnam, and Nixon was looking for a way to pay back New Delhi.

However, the biggest factor was China. Nixon knew that only a breakthrough in Beijing would salvage his presidency and rescue him from the proverbial dustbin. He was, therefore, prepared to bet the farm on this one factor. Besides, in his view, the humiliation of an American ally by a Russian ally would send the wrong signals to the rest of the world.

To get an idea of Nixon’s intent in despatching the Enterprise, see this still partly censored excerpt from the Nixon-Chou meeting.

Nixon: “In December when the situation was getting very sensitive in the subcontinent – I’m using understatement – I was prepared… (sanitised).”

Since Nixon was by all standards a crook and a braggart, he may have well said he was prepared to nuke India.

(During their December 15 conversation in Washington DC, Nixon and Kissinger had given plenty of indication of their desperate intent. Having received a guarantee from Brezhnev that the Indian Army would not advance into West Pakistan, the US duo is in a triumphant mood.)

Nixon: How do you do it?

Kissinger: It’s a miracle.

Nixon: How do you get the formalisation of letters between Brezhnev and me [unclear].

Kissinger: It’s an absolute miracle, Mr President.

Nixon: Did you try to work that out? That we – I’d like to do it in a certain way that pisses on the Indians without, you know what I mean? I mean, we can’t [unclear] we have an understanding, an understanding with West Pakistan. Well, I don’t know. If you think it’s a good idea. I – don’t ask me.

Kissinger: No, I think it’s a good idea. But we have – I have this whole file of intelligence reports, which makes it unmistakably clear that the Indian strategy was –

Nixon: To knock – oh, sure.

Kissinger: – to knock over West Pakistan.

Nixon: Over the line of control here. Most people were ready to stand by and let her do it, bombing Calcutta [sic] and all.

Kissinger: They really are bastards.

Nixon: The son-of-a-bitch [unclear] –

Kissinger: Now, after this is over we ought to do something about that goddamned Indian Ambassador here going on television every day –

Nixon: He’s really something.

Kissinger: – attacking American policy. And –

Nixon: Why haven’t we done something already?

Kissinger: And I – I’d like to call State (Department) to call him in. He says he has unmistakable proof that we are planning a landing on the Bay of Bengal. Well, that’s okay with me.

Nixon: Yeah, that scares them.

Kissinger: That carrier move is good. That –

Nixon: Why, hell yes. That never bothers me. I mean it’s a, the point about the carrier move, we just say fine, we had a majority. And we’ve got to be there for the purpose of their moving there. Look, these people are savages.

Kissinger: Mr President, an aggregate –

Nixon: ….we cannot, the United Nations cannot survive and we cannot have a stable world if we allow one member of the United Nations to cannibalise another. Cannibalise, that’s the word. I should have thought of it earlier. You see, that really puts it to the Indians. It has, the connotation is savages. To cannibalise –

Kissinger: Mr President –

Nixon: – and that’s what the sons-of-bitches are up to –

Gunboat Diplomacy

The Enterprise incident reinforced the image of the “Ugly American” in Indian minds. The political leadership became intensely anti-US too. The incident is reminiscent of the behaviour of former colonial powers.

Commander Mishra wonders whether the US could have gained much more by doing nothing. “Considering the international milieu where its stock was low by the Vietnam overhang, the emergence of a technologically improved and numerically robust Soviet Navy under Admiral Gorshkov, and the necessity of sending a reassuring signal to its allies, mandated some visible proof. The naval deployment was a gesture of solidarity for a formal ally (Pakistan) and an indicator to a future partner (China) that the US could be relied upon to abide by its formal commitments.”

At the same time, the incident highlights the impotence of US sea power against the gains made by a determined India on the ground. “Another takeaway from 1971 is that ‘strategic punditry is no substitute for tactical aggressiveness’ and, hence the importance of professional skill sets,” Mishra notes. “The importance of a cogent national/military strategy is paramount; nevertheless, it needs to be complemented in equal measure by decisive force application at operational and tactical levels.”

Strategic Spinoffs

The 1971 War had several strategic lessons – especially in the area of sea power – for India. The brilliant performance of the Indian Navy in setting ablaze Karachi led to a sea change in the political leadership’s thinking regarding sea power. The navy had hit Karachi not once but twice. A third strike to completely obliterate the port didn’t happen as the war ended too quickly.

Task Force 74’s menacing move convinced India about the need to have assets at sea to counter a threat of this nature. Observing how effectively the Russian subs had enforced a naval blockade and stopped the American fleet, India’s political leadership quietly gave the green light to the nuclear submarine project.

There were other valuable spinoffs from the war. Not only did it change the political geography of South Asia with the creation of Bangladesh, but according to Mishra, it gave a jolt to the supremacist psyche harboured by the Pakistan military vis-à-vis the Indian armed forces.

Never again would the Pakistani Punjabis and Pathans say that one Pakistani soldier was equal to 10 Indian soldiers. After the resounding defeat and the capitulation by 93,000 soldiers – unheard of in military history – the Pakistani military leadership gave up the idea of defeating India militarily and instead focussed on Islamic terror as a weapon against its Hindu neighbour. This would end up injecting the toxic element of jihad into the Pakistani body politic, further weakening the artificial country’s foundations. As Pakistan’s obsession with jihad continues to drain its economy, society and education of vitality, the country has become a caricature that is getting hollowed out. That is one of the key gains of the 1971 War.

–The writer is a globally cited defence analyst. His work has been published by leading think tanks, and quoted extensively in books on diplomacy, counter terrorism, warfare and economic development. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda